Five years since the launch of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), 2020 presented an opportunity to assess the significant global and regional progress toward the goals and identify new pathways for development and economic growth. In fact, in January 2020, after a brief period of decelerated growth, the World Bank projected that global economic activity would not only rebound but strengthen and present growth and investment opportunities around the world—notably in Africa. However, COVID-19 has presented an unforeseen shock, risking many African nations’ development goals and threatening to exacerbate instability.

While undoubtedly disruptive, COVID-19 has illuminated key factors that have contributed to local resilience and stability across the continent, as well as offered insight into the businesses and supportive mechanisms that have helped many African countries keep the coronavirus case and death rates relatively low. With national governments’ resources constrained, lockdowns limiting movement, and global supply chains disrupted, local businesses have proven ever more essential to goods and services delivery, and they provide socioeconomic resilience within and across communities. Understanding how local businesses have responded during this crisis, the factors contributing to resilience amid volatility, and the catalytic impact seed funding and working capital has had on community-driven projects not only sheds light on the importance of development assistance, but also on the partnerships that can effectively and efficiently support local businesses to scale.

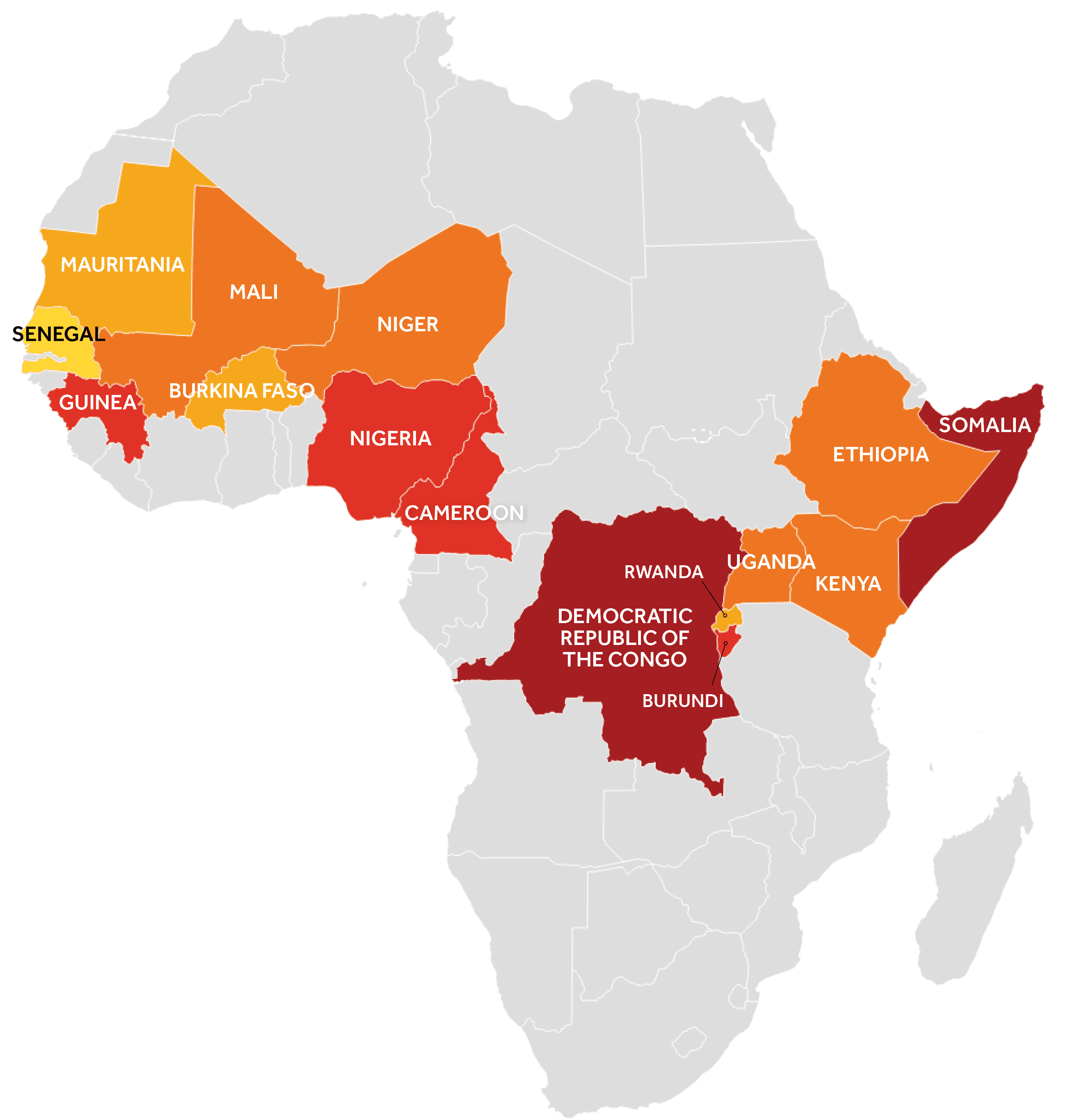

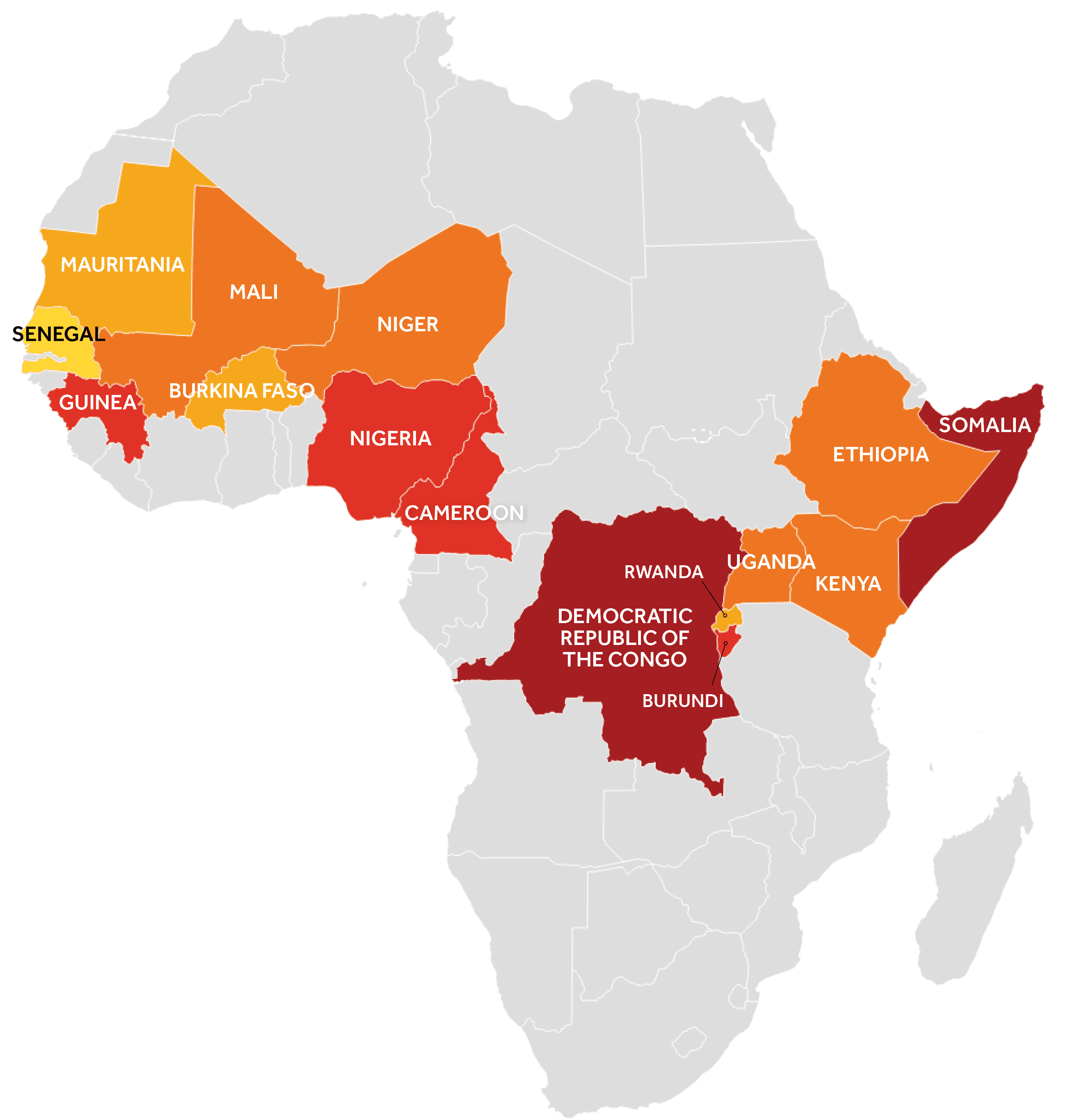

Six months after the first reported cases of COVID-19 in Africa, FP Analytics interviewed more than 50 entrepreneurs, all grantees of the United States African Development Foundation (USADF), about their businesses, work in their communities, and capacity to respond to the needs of their communities during the pandemic. This report marries these first-hand accounts with project-specific data from USADF grants across the Sahel, the Great Lakes, and the Horn of Africa— three of Africa’s most fragile regions—to identify community-led responses to the coronavirus, highlight locally driven projects contributing to resilience and stability, and illuminate opportunities for future public-private collaboration to scale.

View Executive SummaryExecutive Summary

While foreign assistance is failing to keep up with growing needs amid a global pandemic, one approach to supporting the world’s most vulnerable communities succeeds in driving a sizable impact with relatively small-scale grants. As part of a collaboration between the U.S. African Development Foundation (USADF) and Foreign Policy Analytics (FPA), FPA appraised the effect of USADF grants on local entrepreneurship and small- and medium-sized businesses’ contributions to resiliency, stability, and security across the Sahel, the Great Lakes, and the Horn regions of Africa. Through quantitative and qualitative analysis of more than 1,120 USADF grants across the three regions, and interviews with more than 50 grantees in agriculture, off-grid energy, and youth-entrepreneurship, FPA found that community-led development grants play a critical role in fragile communities across the African continent, creating jobs, filling gaps in public service delivery, and acting as a force for stability in conflict areas. Amid COVID-19 and a global economic downturn, community-led funding models are helping to close a major development finance gap.

Even before COVID-19, the landscape of international aid was shifting, creating challenges for developing countries confronting poverty, conflict, and environmental degradation. In recent years, multilateral institutions have repeatedly failed to meet aid fundraising goals for programs across the world, threatening advances already made and hindering nations’ collective ability to meet the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, among others. In addition, development professionals and aid recipients alike have questioned the value of traditional international development models and called for alternative approaches, including more collaboration with the private sector in target countries and around the world. Funding is often short-term, limiting initiatives’ capacity to scale, and financing mechanisms are often rigid, curtailing the flexibility needed on the ground to respond to changing dynamics and emergencies. Also, limited local expertise among funders and program officers can result in projects that do not adequately target the most pressing needs. The COVID-19 pandemic has only emphasized the urgency of these discussions, as emergency programs face funding shortfalls, and major donor countries—such as the U.S., the world’s largest individual contributor of official development assistance (ODA)—reassess their budget priorities after a tumultuous and unpredictable year.

More than half of U.S. ODA goes to sub-Saharan Africa, home to some of the world’s most fragile and conflict-afflicted states, and much of that to the agricultural sector, the continent’s largest employer. Development aid is particularly vital to these fragile states, which—in addition to unique stressors—face the common challenges of poor governance, weak public services, food insecurity, and stagnant economic growth. Although it comprises just a small fraction of U.S. ODA to Africa, the USADF model, which deploys startup and expansion grants to African small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the Sahel, the Great Lakes and the Horn of Africa, represents a viable approach to development aid that fosters local capacity and could be replicated widely.

FP Analytics’ report lays out the key factors and attributes of the grassroots funding model that USADF embodies and that have contributed to local resilience and stability across the continent. The analysis also provides insight into the businesses and supportive mechanisms that have helped many African countries keep coronavirus case and death rates relatively low since the pandemic began. With national governments’ resources constrained, lockdowns limiting movement, and global supply chains disrupted, local businesses have proven ever more essential to goods and services delivery, and they provide socioeconomic resilience within and across communities. Specifically, the analysis points to the effectiveness and efficiency of grassroots-focused funding models and outlines a range of partnerships that can further support local businesses to scale. FPA’s analysis found that:

- Relatively small-scale grants can provide a sizable, direct return: Data analysis found that for every $10,000 in USADF grant funding, 25 workers were hired in agriculture; 19 in youth-led enterprise, and 79 people were connected to electricity. Research suggests that development projects that create new jobs have multiplier effects, increasing the job creation by up to sevenfold through indirect and induced effects. Also, connection to electricity, in particular, has both observed and anecdotal multiplier effects—increasing productivity and enhancing educational and health outcomes.

- Locally driven small- and medium-sized businesses are among the best positioned to fill governments’ capacity and service-delivery gaps, and they are a force for stability across fragile states: Despite making clear progress on a number of development indicators (as measured by the World Bank) including GDP/capita, trade as a share of GDP, infant mortality rates, and secondary education completion rates, the countries USADF targets are still “fragile.” These countries, which have ranked at the bottom of rankings like the Global Fragility Index for years, experience high levels of corruption, unequal economic development, and poor public services. Through locally driven, grassroots-focused entrepreneurship, USADF grantees are filling gaps in public service delivery—from health care to electricity—increasing autonomy and self-reliance, and doing so in remote and hard-to-reach areas: 80% of interviewees agreed or strongly agreed that USADF grantees operate in locations that would not otherwise get funding.

- Locally designed, community-driven funding models help to bridge a major development finance gap: Analysis by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development found that just 6% of official development aid (ODA) to extremely fragile states, and 15% of ODA to fragile states, is deployed to develop economic infrastructure and services. USADF’s sharp focus on economic activity and small business growth is, therefore, filling a much-needed gap in funding to fragile states and providing support that entrepreneurs in fragile states are not receiving from other sources: 74% of interviewees agreed or strongly agreed that USADF funds projects that would otherwise not receive funding.

- Grant flexibility has enabled grantees to pivot operations to address acute needs amid the pandemic: 88% of grantees interviewed agreed or strongly agreed that USADF’s assistance has enabled them to focus more directly on urgent COVID-19-needs and provided important bridge-funding to enable business continuity. This help, according to interviewees, not only stems from the deployment of emergency funds, including those under the CARES program, to those in need, but also from long-term capacity-building support that is helping businesses plan for and adjust to altered market dynamics post-COVID-19.

- Local staff are critical to grantees’ success: Local staff and implementing partners deploy their knowledge and experience of local contexts to forge trusting relationships with grantees, supporting them in crafting applications, building capacity, and launching sustainable and effective projects based on grantees’ local needs and expertise. These local networks are also integral to foreign partners seeking to expand investment in the region.

From these findings, FP Analytics identified a range of opportunities to further amplify the volume and impact of locally designed and locally driven funding models through expanded grant-making, capacity-building, training and support. Relevant stakeholders include:

- African Governments: Match funding partnerships with African governments, which represented around 19% of USADF’s total grant investment between 2015 and 2019, could expand investment in entrepreneurship while enabling African governments to deploy funds targeted at their development priorities and strengthen their interventions.

- African Investment Community and Private Sector: Public-private partnerships (PPPs) enable African businesses and investors to expand their reach and raise their profile while contributing to the growth of the African economy. PPPs also help grantees to establish mixed-funding models that build up credit history and strengthen relationships with African businesses.

- African Non-Governmental Organizations: USADF’s network of local implementing partners has been key to providing hands-on support to grantees, particularly in fragile contexts where the presence of U.S. and international aid workers may be inhibited—such as during COVID-19. Alliances with African NGOs specializing in business development and capacity-building into its network could expand the network of reliable local partners that could benefit greatly from such institutional support.

- International Philanthropic Foundations and Development Institutions: Foundations with a focus on agriculture, off-grid energy, and youth-entrepreneurship in particular could augment existing grants and capacity-building programs by offering their training and expertise to strengthen grantees business know-how and scale their operations. Institutions with limited or no experience operating in Africa can also use the knowledge and expertise of USADF and its local partners.

- International Private Sector: Companies working in relevant sectors, or focused on enhancing business productivity and processes, can offer their services pro bono or at low cost to grantees seeking to professionalize their staff, business structures, and processes. Businesses can deploy their expertise and profits to fortify the autonomy and self-reliance of fragile state economies, and develop a strong local private sector in those countries.

- U.S. Government International Development Agencies: The Global Fragility Act presents an opportunity for greater collaboration among U.S. government agencies and the streamlining of efforts based on organizational expertise and strengths. Aid agencies can build on their collaborative work in Africa, including Power Africa, W-GDP, and the Sahel-Horn Off-Grid Energy Challenge to enhance their development priorities.

Despite challenges, countries in the Horn of Africa, the Great Lakes, and the Sahel have all made steady progress on numerous development indicators over the past two decades and have demonstrated resilience amid COVID-19. Small businesses and local entrepreneurs are continuing to improve public health, extend energy access, expand their economies, and develop critical job skills to strengthen human capacity by focusing on young people—all while grappling with the effects of corruption, violence, and overall state fragility.

By supporting strategic sectors within fragile countries with small, targeted grants, community-led models such as USADF’s create meaningful and lasting impacts at the grassroots level with relatively small per-project investment. Key to all this is the unique focus on entrepreneurial leadership, which relies on local knowledge and expertise, fosters community engagement, and shows a willingness and commitment to investing in projects and areas that others may not. Further collaborations with public, private, and nonprofit partners, such as those outlined above, stand to amplify the model’s impact and foster greater stability and prosperity for this promising region.

CloseState Fragility Hampering Progress, Elevating Role of Local Businesses

Since the onset of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals project in 2000, global development actors and the private sector have been working together to reduce global fragility and achieve key poverty reduction and stability goals. Clear progress has been made, improving quality of life and boosting economic growth on the continent. Across all three regions, infant mortality has decreased dramatically, effectively halving since 2000—dropping from 94.8 to 41.6 deaths per 1,000 births in the Great Lakes, from 83.4 to 48.8 deaths in the Horn of Africa, and 90.4 to 55.3 deaths in the Sahel. Meanwhile, the completion rate for secondary education has been climbing steadily, suggesting an increasingly capable labor force. In the Great Lakes, completion has risen from just 14.9% of the cohort in 2000 to 32.9% in 2018, and similar progress has been reported in the Sahel in the same period. Data on the Horn of Africa is scarce, however. Finally, while GDP growth has dropped slightly since 2018, GDP per capita has increased significantly in all three regions since 2000. Productivity in the Great Lakes has increased by 125.2%, in the Horn by 207.4%, and in the Sahel by 95.2%, as has trade as a share of GDP.1

GDP Per Capita Steadily Increasing

GDP/capita in US dollars

- The Great Lakes

- The Horn of Africa

- The Sahel

Infant Mortality Rapidly Declining

Infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births

- The Great Lakes

- The Horn of Africa

- The Sahel

Electrification Rising Steadily

% of population with access to electricity

- The Great Lakes

- The Horn of Africa

- The Sahel

Human Capital Improving through Rising Education Levels

% of relevant age group completing lower secondary education

- The Great Lakes

- The Horn of Africa

- The Sahel

Missing data for Horn of Africa for the following years: 2000-04, 2006-07, 2011, 2013, 2017-18.

Despite this progress, many of the countries in these three regions are considered “fragile.”2 Their risks are context-specific and multidimensional, but, according to a range of international organizations, the nations share characteristics of weak institutions and poor governance that limit capacity to provide goods and services and contribute to economic isolation and disruption—risking conflict and instability.3 African nations across the Sahel, Horn and Great Lakes regions are among the most fragile in the world, according to the Fund for Peace’s Fragile States Index.4,5 The countries in these three regions consistently scored poorly on all subcategories on the Index, but particularly on demographic pressures and provision of public services, two aspects of fragility particularly relevant in Africa, where a rapidly growing youth population coupled with weak governance have contributed to underemployment, lack of productivity, and waves of criminality and violence.6 Numerous research studies examining the determinants of fragility in countries emphasized the key role state institutions, particularly civil liberties, play in stability.7

USADF Grants Target Projects in Africa’s Most Fragile Countries

The Fragile States Index measures national cohesion factors, economic factors, political factors, and social and demographic factors. Lower scores reflect more stability. The 2020 scores range from 14.6 (Finland) to 112.4 (Yemen).

Fragility is the result of multiple factors, including food supply, access to clean water, socioeconomic instability, public services provision, human rights protections, and state legitimacy. Accordingly, successful mitigation strategies must adopt integrated, holistic approaches to addressing fragility that combat multiple stressors and have positive multiplier effects from their use. Targeted programs that help improve energy efficiency and agricultural production, and provide skills to young people that they can use to create businesses, for example, can have cascading benefits on socioeconomic welfare and stability.

Hover over map regions for more information.

This map is available with interactive features on desktop.

Warning Alert

Nations & Communities Demonstrating Resiliency in the Face of COVID-19 Shocks

Early in the pandemic, experts and analysts anticipated that COVID-19 would have a catastrophic impact in Africa, where ongoing conflict and a series of infectious disease outbreaks—most notably Ebola—have degraded medical infrastructure and strained professionals8, and from where an estimated one-fifth of doctors emigrated to high income countries between 2005 and 2015.9 As a result, the continent had an average of just 1.3 health workers per 1,000 people, according to the World Health Organization—well below the SDG goal of 4.5 per 1,000, with African nations experiencing the most severe health care worker shortage in the world.10 Despite this, with a few exceptions, African nations have demonstrated remarkable resilience, keeping case and death rates low with proactive prevention policies and the application of health professionals’ wealth of knowledge in containing infectious diseases. As of October 2020, the Great Lakes, the Sahel, and the Horn of Africa had a cumulative average of 489 cases per 1 million people, compared to a global average of 7,882 cases per 1 million, since the pandemic started. These regions of Africa were performing even better in keeping deaths to a minimum, experiencing just 8.7 deaths per 1 million, compared to a global average of 147.9.11

However, COVID-19 has exacerbated long-standing development challenges, as the ongoing coronavirus and economic downturn threaten income opportunities for millions across Africa and fragile countries in particular. Coronavirus-related restrictions have devastated the informal economy— the primary generator of economic activity and the source of 86% of African jobs (including 89% of female employment)12 —and containment policies have often been violently enforced by police forces and the military.13 Border closures and flight groundings have disrupted informal and formal supply chains, hindering both small-scale cross-border trade and high-volume commodity exports, leading the World Trade Organization (WTO) to predict an 8% decrease in exports and 16% decrease in imports across Africa in 2020.14 These immediate impacts set back progress toward key development goals by creating widespread food insecurity, loss of income, and civil unrest.

USADF Regions

Click on a region to learn how it has been affected by COVID-19.

The Sahel averaged 619 COVID-19 cases and 11.8 deaths per 1 million people as of October 2020, compared to a global average of 7,882 cases and 148 deaths per 1 million people, since the pandemic began.15 The region has also experienced a prolonged period of violence between state forces and insurgent terrorist groups, beginning with the Boko Haram insurgency in 2009, which has increased fragility in the region through displacement, violence against women, and attacks on schools and hospitals, and has spread and inspired other groups.16 Many of these groups have recruited fighters from among the large numbers of unemployed youth who distrust their governments and are often the victims of violent government anti-insurgency crackdowns.17,18 Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), one of the most active militant groups in the region, regularly exploits and absorbs local criminal networks that flourish in remote and peripheral areas, where government resources often do not reach, exacerbating existing fragility.19

Mali, where much of the unrest is concentrated, has deteriorated in recent years, along with its immediate neighbors in the Sahel. All rank near the bottom of the UNDP Human Development Index because of their ongoing conflicts and their respective impacts.20 In addition to the immediate threat to lives and livelihoods of insurgent violence, these ongoing conflicts have significantly degraded health infrastructure across the Sahel, hindering states’ ability to effectively treat and isolate coronavirus patients. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) estimates that nearly 250 hospitals in Burkina Faso, Mali, and western Niger are nonoperational because of violence, and more than 80% of the region’s remaining health centers are in Nigeria, also the richest country in the Sahel.21 The instability places added pressure on small-scale, local capacity to meet the health-related needs of communities not benefiting from government intervention or development work, but likewise presents opportunities for local entrepreneurs to apply their solutions to meet local needs.

Despite cases and deaths remaining relatively low, the impacts of the pandemic on the region have been acute: Save the Children reported in early October 2020 that nearly 5 million children in Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, and Chad urgently needed humanitarian assistance, as families struggle to earn money while reducing their exposure to the coronavirus.22 Widespread hunger could bring an increase in malnutrition and preventable disease, further straining the region’s already overextended and deteriorated health infrastructure, and create new sources of instability as people migrate to new areas or are forced to rely on insurgent groups for food and income.23

CloseThe African Great Lakes are leading by example in their pandemic response, particularly in Rwanda, which has implemented a science-forward approach by developing an effective rapid test and using robotics and technology to minimize contact between doctors and patients.24 This approach is working: As of October 2020 the Great Lakes averaged just 167 cases and 1.8 deaths per 1 million people since the pandemic began.25 It is also modeling success in COVID-era electoral politics, as Burundi became the first country in Africa to execute a successful transfer of power after its general election in May.26

However, violence in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the catastrophic impacts of climate change are driving food insecurity and displacement within the region, exacerbating instability brought by the pandemic. In late 2019, UNOCHA reported that the region was home to 17.8 million severely food-insecure people, of whom 15.6 million were in the DRC,27 and now the World Food Program is reporting 500,000 refugees in Uganda at crisis hunger levels as a direct result of cuts to food aid and coronavirus-related restrictions that are preventing food delivery.28 The DRC, where the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) found that violence had increased by 18% in 2019,29 is home to nearly 5 million internally displaced people who are at particularly high risk of contracting the coronavirus or another infectious disease.30 Displacement camps tend to be temporary structures that are densely populated and have little reliable sanitation.31 Entrepreneurs working with displaced populations have reported being unable to access camps and settlements that have been closed off to prevent the spread of coronavirus. This measure has not only restricted freedom of movement and access to necessary resources, but also prevents displaced people from engaging in small-scale economic activity that would increase their independence and purchasing power. Despite these challenges, several entrepreneurs interviewed for this study are trying to reverse acute situations on the ground— responding to the urgent needs of displaced people amid the crisis and supporting economic activity via skills training and off-grid energy supply projects.32

CloseIn the Horn of Africa, resource competition at the intercommunal and international levels and coronavirus containment efforts are reducing agricultural productivity and threatening to increase food insecurity across the region. As of October 2020, the region averaged 679 cases and 12.2 deaths per 1 million people since the pandemic began,33 higher than either the Sahel or the Great Lakes. Governments in the region have been criticized for heavy-handed enforcement of restrictions, particularly in Kenya, where security forces have been accused of whipping and killing civilians who violated curfew restrictions in the early days of the pandemic,34 and in Ethiopia where tensions have already been rising with Egypt and Sudan over management of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and resource-sharing along the Nile.35

This large-scale competition over resources is being mirrored at the grassroots level, where pastoralists and farmers have been known to resort to violence over increasingly scarce land. In 2015, the last year for which data is available, an estimated 38 million inhabitants of the Horn of Africa were pastoralists, with livestock exports exceeding $1 billion per year,36 yet large-scale infrastructure projects, and now pandemic-related border closures, are preventing pastoralists from caring for their herds and driving some out of work entirely. In addition, recent locust swarms and prolonged drought have destroyed crops and exacerbated food insecurity in the region, with the International Rescue Committee (IRC) reporting that 19 million people in Ethiopia alone needed humanitarian assistance before the onset of the civil conflict with the Tigray Region, which has caused new flows of refugees into Sudan.37

The region is still heavily reliant on agriculture, with the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimating that between 70% and 85% of the region’s population works in agriculture or pastoralism,38 yet productivity is very low because of small tracts of land and limited capacity to scale, as well as lack of irrigation or agronomy knowledge.39 Resources are only likely to grow scarcer because the region’s population is predicted to double by 2040; more than 70% of the population is now under 30 and underemployed.40 Crucially, small businesses in the region are working to enhance agricultural productivity by investing in vocational and entrepreneurship training for youth, with the aim of supporting them to find reliable work or establish businesses of their own. However, strictly enforced lockdowns and individuals’ decreased spending power are threatening the survival of these small informal businesses—making support from the public and private sector exceptionally critical.

Close

Local Businesses: Key to Managing COVID-19 and Contributing to Regional Growth & Stability

In fragile contexts, employment and economic growth are vital to stability, contributing to a virtuous cycle in which increasingly stable environments create an enabling environment for new businesses and foreign direct investment (FDI) and expanded economic opportunities. Reliable employment, higher productivity, and business tax revenue help to mitigate violence and increase community resilience.41

Strengthening and scaling Africa’s formal economy, including by supporting small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), offers a powerful strategy to reduce poverty and violence within these fragile states. In addition to addressing the immediate needs of individuals and their families, the United Nations emphasizes the importance of reliable, contract-based, permanent employment, including through the promotion of entrepreneurship, in achieving decent work and economic growth that is embodied in Sustainable Development Goal #8.42 Additionally, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), grassroots economic activity can reduce fragile states’ dependence on official development aid (ODA), remittances, and debt, all of which are now under threat as a result of COVID-19’s global impact.43 Given the highly localized and contextual nature of fragility, local businesses are more likely to understand community needs and can drive the engines of economic activity across the continent. As this report will show, local entrepreneurs and SMEs are among the best positioned to identify needs within their communities and contribute to economic growth and stability, but their survival depends on targeted support and technical assistance enabling them to expand and generate sustainable revenue streams.44

However, entrepreneurs interviewed for this report across all three regions expressed that pandemic-related restrictions are threatening small businesses, reducing productivity, and hindering progress on development goals. Marketplace restrictions and social distancing measures have resulted in widespread losses of income, both for individuals and their families, particularly those in rural areas who are highly dependent on the income earned by urban migrants. This loss of income reduces spending, threatening the survival of SMEs and increasing the threat of radicalization as unemployed and idle youth turn to extremist and insurgent groups for a regular paycheck and food supply. The ILO has predicted that as many as 25 million jobs worldwide may be lost as a direct result of the pandemic,45 which would be catastrophic to economic development in Africa, which requires the creation of 10-15 million new jobs per year to keep pace with demographic growth.46 FDI into Africa is also predicted to drop sharply this year; threats to profits and delays to projects may encourage investors to focus on their respective domestic markets. Analysts forecast a 30% drop in FDI into sub-Saharan Africa in 2020, further contracting the availability of jobs and investment for new and existing businesses.47 These dynamics make direct support to local SMEs, such as that being provided by USADF, ever more important.

Agricultural cooperatives are also enhancing economic and physical security for women. Women Farmers Advancement Network (WOFAN), a rice-growing cooperative in Nigeria, was established specifically to create economic opportunities for women in rural areas. Since its establishment in 1996, WOFAN has grown from a collective of just 28 women to a network of self-governed cooperatives with 45,000 male and female members across northern Nigeria. They have access to microcredit, leadership and business training, and the necessary equipment to process and package their rice crops for sale. Their recent USADF grant has more than doubled crop yields by enabling members to farm in both the rainy and dry season because of enhanced agricultural techniques and irrigation equipment.66 While the cooperative now also employs men as well, its core mission of supporting women remains dominant.67 Such projects have been found to reduce the risk of domestic violence and poor health outcomes, and improve community development because the women increasingly reinvest their earnings into education and infrastructure development.68

Providing Vital Resources and Addressing Food Insecurity Amid COVID-19

Throughout crises brought on by the coronavirus pandemic, cooperatives have taken on a new role as trusted community institutions, using their deep local ties to promote COVID-19 prevention and care for vulnerable people. Many of the cooperative members interviewed have made use of emergency grant funding from USADF and other development bodies to buy hand sanitizer, face masks, and cleaning supplies to distribute to members and local families, and they are communicating health and safety information. In addition, while many cooperatives are struggling to sell their produce amid travel restrictions and market closures, they are pivoting to become community food hubs, selling food packages at reduced prices or giving them away to those in need, and extending access to useful equipment. Kweyo Growers, a Ugandan peanut-growing and peanut butter-producing cooperative, for example, has established a new income source amid the pandemic by renting out its two tractors to other farmers in the area who are still harvesting crops. Its general manager, James Otim, credits the cooperative’s quick pivot to tractor rental to its work with USADF, which, in addition to providing the grant funding to buy another tractor, taught him that “it’s all about planning and preparation…whether that’s in starting a business, advising, investment” or expanding business activities.69

The pandemic has also shown many cooperatives the importance of increasing local productivity and reducing African reliance on imports. Trade and supply chain disruptions, movement restrictions, and logistical challenges spurred by COVID-19 have exacerbated food insecurity in Africa, which imported 85% of its food between 2016 and 2018, at an annual cost of $35 billion.70 Cooperatives are working to increase productivity, move up the agricultural value chain and become more vertically integrated. And several USADF-supported cooperatives are building regional markets by organizing with other cooperatives. Ndumberi Dairy Farmers Co-operative Society Ltd., a dairy collective in Kenya long reliant on selling its milk to third-party packaging companies, is bringing its packaging operation in-house and selling directly to supermarkets,71 while Sangara Agro Allied Producers and Marketers Cooperative Association (SAAPMCA), a Nigerian groundnut cooperative, has begun selling its produce door-to-door in local communities instead of relying on an expensive courier service.72 Taking its commitment to collectivism even further, Nigerian cooperative Agriculture and Value Addition Multipurpose Cooperative Union (AVAMCU) has begun a co-selling and franchising strategy that enables it to sell its products in distant communities through other cooperatives’ shops, reaching new customers through preestablished relationships, and offering the same in return to other cooperatives, to strengthen and expand the market for African-grown products.73

Off-Grid Energy: Connecting Homes and Businesses to Reliable Electricity

Energy access, a key aspect of development and a crosscutting SDG, is critical to improving quality of life, reducing violence, and stemming environmental degradation74 —and is one of the primary sectors receiving USADF support. Across the Sahel, the Great Lakes, and the Horn, access to electricity has increased significantly since 2000 because of national grid expansion and the growth of the off-grid energy industry. By 2018, the percentage of people with access to electricity had grown to 44.7% in the Sahel, 28.6% in the Great Lakes, and 51.7% in the Horn, compared to 23%, 6.6%, and 14%, respectively, in 2000.75 However, 600 million sub-Saharan Africans still lack access to electricity; the region is home to 75% of the world’s remaining population without electricity.76 Charcoal and other biomass fuels are used in 70% of sub-Saharan Africa,77 which harm health and the environment. The WHO estimates that about 3.8 million people around the world die prematurely each year as a result of household air pollution caused by these practices,78 with almost 5% of these deaths in Africa.79

Energy Grants

Click to view data by country within each region

The Sahel

$2.47M 34 total grants

The Sahel

$2.47M 34 total grants

- Burkina Faso $94.09K 1 total grants

- Mauritania $99.91K 1 total grants

- Nigeria $2.28M 32 total grants

The Great Lakes

$1.99M 16 total grants

The Great Lakes

$1.99M 16 total grants

- Rwanda $12.83M 6 total grants

- Uganda $23.88M 10 total grants

The Horn of Africa

$3.13M 27 total grants

The Horn of Africa

$3.13M 27 total grants

- Ethiopia $1.04M 10 total grants

- Kenya $1.84M 16 total grants

- Somalia $238.19K 1 total grants

In this environment, suppliers of low-cost, renewable energy technologies are connecting underserved communities in both rural and urban areas to electricity and clean fuel sources, boosting economic activity and job creation while enhancing health and environmental outcomes.80 Particularly in rural areas where prospects of grid connectivity are remote, renewable energy can be transformative, whether in the form of individual home energy kits and solar panels, or mini-grids capable of powering communities—most of which still require subsidies from government or international development agencies to be viable.81 USADF has been engaged in off-grid energy projects in the region for nearly 30 years. Since 2007, USADF has invested in 7,761 grants focused on off-grid energy, for a total of $7.6 million across all three regions.

Local SMEs Supplying Clean and Healthy Energy Alternatives

Solar energy has transformed many communities, providing light and electricity to homes and improving health outcomes and quality of life. USADF-funded entrepreneurs interviewed by FP Analytics underscored the benefits of solar access for women in the region who predominantly cook and care for their families, and spend hours each day cooking with coal and kerosene.82, 83 An in-depth analysis of the Rwandan government’s program to increase energy access via off-grid infrastructure found that the affected households reported significantly improved in air quality in their homes after shifting away from kerosene lamp usage.84 A more affordable and sustainable energy source than batteries and kerosene, solar has reduced household spending on energy. It has also enabled greater productivity throughout the evening and nighttime hours, and increased children’s ability to study and do homework in the evenings. Interviewees described growing up in homes where kerosene lamps were the only source of light, and respiratory illnesses were common, noting that these hardships inspired many of their business plans.

Off-grid Energy Generating Economic Activity

In addition to providing direct sources of power, USADF-funded off-grid energy businesses are generating economic activity in the areas they serve by providing energy to rural and urban businesses, establishing local manufacturing hubs, and creating reliable employment through networks of sales agents, couriers, and technicians. Research has shown that aid for renewable energy generates other multiplier effects and can produce a significant number of direct, indirect, and induced jobs,85 and improve economic development through increased spending and demand from local supply chains. Economic benefits also come from extended operating hours.86

Nigerian entrepreneur Habiba Ali’s company, Sosai Renewable Energies Company, represents a powerful case study. Since establishing her company in 2010, Ali has provided solar energy components and improved cookstoves to nearly 600,000 people and has installed three solar mini-grids capable of powering entire villages. As a key component of her commitment to reaching underserved and remote communities, Ali provides energy components on a pay-as-you-go or pay-to-buy basis that helps her customers avoid debt and access energy despite a lack of formal lines of credit, as do other entrepreneurs working in this sector.87 Expanding her business from the ground up, Ali trains women and vulnerable youth to work as sales agents, couriers, and installation and maintenance technicians within their communities, using local connections to expand her business. Ali sees this strategy as a key generator of income in northern Nigeria. Also, women’s consistent incomes establish them as family leaders, reducing domestic violence and serving as a first line of defense against Boko Haram recruitment tactics. According to Ali, “We as women can actually change a community if we have the power to bring up our kids properly… and the way [we] can have that power is when [we] have economic strength.”88

While solar products could transform Africa, most equipment is still imported.89 Recognizing that import dependence creates vulnerability for solar businesses and responding to growing local demand, USADF grantees are working to develop local capacity. Nigeria-based Auxano Solar is promoting the development of a solar equipment manufacturing industry on the continent. Auxano is one of the first companies in Nigeria to manufacture solar panels and other energy components within the country. Since shifting fully into manufacturing in 2016, Auxano Solar has sold about 28,000 solar energy units to consumer-facing African energy companies, equal to around 7 megawatts of power.90 Its owner, Chukwudi Umezulora, plans to expand and establish Nigeria as a hub for renewable energy manufacturing in the Sahel, bringing more of the renewable energy value chain inside Africa.91 Intra-African trade is increasing but remains low, at just 2% compared to 68.1% in Europe and 59.4% in Asia, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). The solar energy environment offers immense opportunities for businesses such as Auxano Solar that are focusing on supplying African companies. Prospects for such businesses were further boosted by the African Continental Free Trade Area that came into force in 2019.92

Building Out Rural Energy Infrastructure

Several USADF-funded entrepreneurs are also focusing on scaling their local power projects by building off-grid community infrastructure such as power stations and mini-grids, which supply low-cost electricity to local businesses and vulnerable groups in rural areas. Power Trust and Raising Gabdho, two USADF-funded solar energy companies in Uganda, are now undertaking electrification projects in remote displacement camps, extending power to homes and local small businesses such as supermarkets, enabling refrigeration of perishable foods and increasing the businesses’ returns.93 Power Trust has already installed a 2-kilowatt mini-grid, and is working with women’s groups in the refugee settlements to better understand their needs for future project design. Meanwhile, Raising Gabdho has installed streetlamps to make walking at night safer.94 Power Trust’s founder Tony Simbwa conveyed the impact these projects will have, noting that “I’m sure that by the time we’re finished it’s going to create jobs, it’s going to change lives, and people are going to have more opportunities in those areas.”95

Rural electrification projects, such as Havenhill Energy, a Nigeria-based company and USADF grantee, are attracting new residents and shifting migration patterns. Newly electrified villages are becoming local hubs for commercial activity and attracting migrants who would previously have traveled to an urban center to find work.96 Off-grid energy hubs are powering a range of other business activity across the regions, from service industries such as hairdressers and retail shops, to industrial mills and processing.97 In addition to the community effects, increasing rural employment and income generation aids stability across the region by minimizing rural-urban migration and densification of urban centers, where much of the employment is informal and unreliable and underemployment and poverty can contribute to dissatisfaction and unrest.98

Powering Communities' Pandemic Response

The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted new avenues for many renewable energy entrepreneurs who are providing local services and amplifying their social impact, which interviewees have undertaken independently and with the help of USADF and other funding bodies. Hospitals and isolation centers that, while often degraded, are necessary to treat COVID-19 patients and prevent further spread as part of African nations’ robust public health response to the pandemic, require consistent and reliable power. But the majority of clinics across these three regions regularly suffer from power outages or remain disconnected from the electrical grid. Off-grid energy companies, such as those interviewed for this study, are filling this gap by entering into partnerships with governments and individual hospitals to provide reliable power. In Mauritania, an off-grid energy company, Companie Generale des Energies Renovables (COGER), has, for example, expanded the impact of its 2019 USADF grant, which funded the construction of a solar power plant in the remote village of Acharim, to supply the local hospital with electricity and support rural health care access.99 In northern Nigeria, Sosai has secured investment from African renewable energy investor All On to supply solar components to hospitals around the country.100

Amid the pandemic, both COGER and Sosai have expanded their business operations and increased revenue, but many companies, particularly those supplying energy kits to individual households, have also chosen to reduce fees and postpone payment plans to supply more customers with energy immediately.101 Makohaa, a social enterprise in Kenya focused on improving health outcomes in rural areas, including through clean energy infrastructure and improved cookstoves, was completing a community-funded rural electrification project when the pandemic hit, reducing the available funds for the project as families lost income and prioritized their immediate needs. Using an emergency grant awarded by USADF, Makohaa chose to complete the electrification project at no charge to the community and connect all households in the village to the grid. While this decision was motivated by social need, Makohaa’s leaders hope that they will be able to recoup the costs of the project to reinvest in more projects in the future. Nearby villages seeking electrification have already reached out to the company after the first project’s success.

Such off-grid energy projects have heightened importance amid the pandemic, with the International Energy Agency (IEA) projecting that energy access in sub-Saharan Africa will decrease significantly as a result of COVID-19—creating direct harm in communities and setting back the achievement of SDG 7, which seeks to ensure universal access to affordable, reliable energy from sustainable sources.102 However, multiple interviewees expressed hope that the conditions of the pandemic would prompt more paying customers to access their services as families and children are confined to their homes, and that greater visibility during this period will serve their businesses well in the future.

Youth-led Enterprise: Harnessing the Potential of this Swelling Demographic

About 60% of Africa’s population is under age 25, and analysts project that one-third of the world’s youth will be concentrated in Africa by 2050.103 Africa’s rapidly growing population, combined with low infant mortality rates, has led to a majority-youth population. These dynamics, coupled with slowing growth, increase risks of un- and underemployment for this cohort. Though only 22% of youth were not engaged in some form of employment, education, or training (NEET) in 2019—meaning that 78% were either in or actively seeking work or education—36% of youth were defined as being in extreme working poverty and were earning under $1.90 per day, on average, according to the ILO.104 This signals that even young people who are finding work are unable to earn enough to support themselves and their dependents.

Entrepreneurship Grants

Click to view data by country within each region

The Sahel

$2.28M 72 total grants

The Sahel

$2.28M 72 total grants

- Burkina Faso $45.00K 3 total grants

- Cameroon $246.08K 10 total grants

- Guinea $50.00K 2 total grants

- Mali $50.00K 2 total grants

- Niger $35.00K 2 total grants

- Nigeria $1.49M 41 total grants

- Senegal $359.50K 12 total grants

The Great Lakes

$2.21M 62 total grants

The Great Lakes

$2.21M 62 total grants

- Burundi $280.00K 4 total grants

- DRC $321.50K 14 total grants

- Rwanda $375.00K 9 total grants

- Uganda $1.23M 35 total grants

The Horn of Africa

$9.58M 88 total grants

The Horn of Africa

$9.58M 88 total grants

- Ethiopia $182.55K 9 total grants

- Kenya $1.02M 37 total grants

- Somalia $8.37M 42 total grants

In addition to concerns for young people’s socioeconomic well-being, these trends have concerned policymakers, academics, and security analysts alike because large underemployed and disenfranchised youth populations have been linked to political unrest and violence.105, 106, 107 Such risks are particularly elevated in fragile states, where government corruption contributes to inequality, and vulnerable youth are prey to recruitment by insurgent and terrorist groups, who take advantage of legitimate grievances and weaponize them against the state, while offering a regular paycheck.108 Out of 176 countries, the Sahel averaged a rank of 118, the Great Lakes 121 and the Horn 135 in Transparency International’s 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index, compared to an average rank of 117 for Africa – putting them at greater risk of unrest and insecurity because of youth dissatisfaction.109 This level of corruption can contribute to fragility and poor economic development because corrupt governments are likely to pursue policies that choose personal interests over national concerns, sacrifice public needs, and undermine public trust between the state and the public. Such conditions, exacerbated by high levels of inequality, can contribute to instability and unrest. Indeed, data from the Fragile States Index mirrors the corruption data, with the average ranks for the three regions similar in terms of state legitimacy, public service provision, and economic inequality as seen in Table 1.110

Table 1: Average Regional Rankings on Key Fragility Metrics

Source: Fragile States Index

Numbers represent the 2019 averages for the countries in the respective regions. Higher numbers represent worse outcomes

While the so-called “youth bulge” is often characterized by risks, this growing demographic also represents a tremendous resource to drive African nations’ economies forward if it is supported and cultivated. Unlike high-income countries such as the United States and much of Europe that have aging populations where the ratio of productive, working people to older adults that are no longer in the workforce is shrinking, African countries’ outsized youth populations represent many years of potential contribution to their economies through productive, fulfilling work.111

Recognizing the need for investment and the potential of this cohort, USADF has invested $14.1 million in 222 entrepreneurship grants since at least 1999. The agency is also notably active in the highest risk environments, where these dynamics risk unrest and insecurity because of youth dissatisfaction and limited opportunity. The grants support entrepreneurs under age 35 to establish businesses for social good, generating economic activity while addressing wider development challenges. These small USADF-supported youth enterprises are having a substantive, outsized impact compared to the size of investment. Youth-led enterprise grantees in the Sahel reached an average of 12,570 beneficiaries or customers over the course of their grants and hired an average of 15 workers, while in the Horn of Africa grantees reached an average of 2,353 customers and hired an average of 273 workers. In the Great Lakes, USADF grantees reached an average of 403 customers and hired an average of nine workers.112 This translates to eight workers hired for every $10,000 in entrepreneurship grant dollars invested in the Sahel, 19 workers hired in the Horn of Africa, and 4 in the Great Lakes.113

Start-Up Funding is Helping to Unleash the Potential of Africa’s Youth

Entrepreneurs interviewed for this study unfailingly emphasized young people’s potential to bring positive social and economic impacts in and beyond their communities; many of them provided examples of youth that are innovating and creating solutions to pressing local challenges. These young entrepreneurs are making targeted interventions at local levels, providing job skills and entrepreneurship training, expanding financial inclusion, and re-imagining rural health care. In addition to the startups’ direct impacts, including generating formal employment, they are increasing vocational skills training and education, elevating worker capacity and productivity, and contributing to community resilience by reducing under-employment and frustration. These young entrepreneurs are also establishing themselves as leaders and trusted and knowledgeable local partners.

In Somalia, for example, where decades of conflict have degraded both governance and the education system, and students are now regularly displaced because of natural disasters,114 youth unemployment is compounded by a widespread lack of literacy and transferable skills. USADF-funded organizations Kaashif Development Initiatives and Candlelight for Environment, Education, and Health, are working to reduce youth unemployment and radicalization by providing transferable skills education and working with local businesses to secure jobs and apprenticeships for their graduates.115 Funding from USADF has allowed them to provide transportation to and from the school, enabling them to reach youth in neglected rural areas, and keep dropout rates relatively low.116 Since 2008, Kaashif has worked with more than 7,000 youth in southern Somalia, supporting them to start their own businesses and helping them secure jobs in information and communications technology (ICT) and construction, while Candlelight has worked with thousands of youth in Somaliland.

Driving Innovation and Digital Financial Inclusion

As roughly 57% of people in Africa, particularly youth, are still unbanked and excluded from the financial sector, according to the World Bank,117 USADF youth grantees are launching businesses that expand access to financial services including bank accounts, credit, and digital sales platforms that promote economic activity while addressing key development challenges. Access to such financial resources is particularly effective for women and youth: A study in Kenya found that providing no-cost savings accounts to female-headed households reduced extreme poverty by 22%, while in Nepal, female-headed households spent 15% more of their earnings on nutritious food, and 20% more on education after receiving free savings accounts.118 As the largest demographic group in Africa, connecting young people with financial resources, bank accounts, and lines of credit can transform these businesses and boost future growth.

Working to increase access to credit and digital inclusion in their countries, youth-led enterprises such as Quest Digital Finance in Uganda and Afrikapu in Kenya are creating digital hubs for buying and selling of farm equipment and services and artisanal goods, respectively. Both are reinvesting their profits into microloan programs that provide lines of credit to people excluded from traditional financial institutions.119 Quest’s platform hosts about 142,000 registered users, and about 23,000 transactions per month.120 Afrikapu works with more than 17,000 women extending microloans and offering business trainings and sells the products of 1,000 women artisans based in Kenya and South Sudan on its website.121 These organizations seek to enable their customers to build up credit through consistent repayment of their microloans, gain access to established banks and scale their businesses. As Quest Digital’s founder Jean Onyait, who has been running his agriculture-focused enterprise for 10 years, noted, “professionally, unprofessionally, some of us were born in these circumstances,” and he is among the best positioned to understand the needs of his farmer clientele and recognize new opportunities that can enhance the lives of Uganda’s rural poor.

Improving Health Outcomes in Rural Areas

Elsewhere, youth are implementing creative solutions to long-term challenges including the lack of access to health care. Kaaro Health, in Uganda, and Nest for All, in Senegal, are working to increase rural access to basic health care such as maternity and neonatal care, with the aim of reducing maternal and infant mortality, to build on both countries’ recent progress.122 Senegal’s infant mortality rate has halved since 2000, dropping from 67 deaths per 1,000 live births to 34 in 2018, while Uganda has had an even more dramatic decrease: from 87 deaths per 1,000 births in 2000 to 35 in 2018. But further progress is necessary for both countries to reach the global average of 29 deaths per 1,000.123 With the help of targeted grants, Kaaro Health and Nest For All are both contributing to closing the gap in infant mortality by providing care to mothers and babies that is closer to home and, with the help of grants, cheaper than other private clinics. In a short time, both enterprises have had notable impacts: Nest for All treated 16,000 patients in 2019, including delivering 600 babies, at a cost to patients 40% lower than other private health clinics in Senegal, while Kaaro Health has established nearly 70 health centers and completed 120,000 clinic visits since 2017. This greater accessibility of health care is helping patients save money that would otherwise be spent on travel and avoid preventable illness and injury.124

Other projects are enhancing health outcomes through community infrastructure. In Rwanda, Iriba Water Group is establishing clean-water infrastructure, including pumps and wells, in remote, urban and peri-urban communities to stop the spread of preventable and waterborne diseases. Just four years after its establishment, Iriba is now providing clean water to 53,000 people per day, via rural water infrastructure projects, urban and peri-urban drinking water fountains, and the sale of water filters to homes, schools, and businesses. In the future, Iriba’s founder Yvette Ishimwe aims to serve 150,000 people per day in Rwanda, before expanding to neighboring countries with high poverty rates, particularly the DRC and South Sudan, where population displacement is high and makeshift settlements often lack reliable sanitation infrastructure.125

Youth-led Enterprises are Pivoting During the Pandemic

While the pandemic and its associated restrictions pose a threat to small businesses, the entrepreneurs interviewed were keen to find creative ways of expanding their reach and supporting vulnerable communities during this period. Iriba Water Group has installed hand-washing stations in neighborhoods across Kigali and distributed soap, hand sanitizer, and accurate information to promote low burden but high impact interventions against the spread of COVID-19.126 Although youth-training enterprises such as Kaashif and Candlelight cannot meet in person, they are finding new creative ways to communicate with their existing beneficiaries and reach out to new ones, including by hosting online webinars and training, and upgrading their facilities to be compatible with government social distancing requirements.127

Interviewees acknowledged the critical role that grant funding has played in developing and launching their businesses—and being able to adjust during the pandemic. They also universally expressed a desire to transition to self-sustaining business model with diversified revenue streams that would enable them to weather future shocks while continuing to support their communities.

Supporting Long-Term Economic Growth in Fragile Contexts

African SMEs and entrepreneurs continue to face challenges, both in the immediate and the long term, but the pandemic has demonstrated that small-scale, agile businesses play an important role in emergency response and long-term economic growth—particularly in fragile states. Helping grantees to weather the uncertainties and challenges of the COVID-era will enhance their ability to survive and adapt to future crises, and position them as strong leaders and partners in regional development and security. This is particularly important for economic development throughout Africa, given the outsized role of SMEs and the informal sector in national economies and as a share of GDP.

USADF grantees interviewed for this report shared similar challenges, regardless of sector or country of operation, highlighting the prevailing barriers that still face SMEs across Africa, and which have been compounded during COVID-19. A number of these issues are common to businesses operating in fragile states, such as poor infrastructure and governance, and difficulty attracting foreign direct investment. But among the most acute challenges are access to startup funding and support to transition to non-grant-based, sustainable financial models. Interviewees were keenly aware that grants and other forms of ODA may not always be available—particularly in light of the pandemic, which is predicted to trigger a widespread reassessment of spending priorities among the world’s largest aid donors. Grantees are working to identify business models, partnerships, and investments that would enable them to strengthen their current initiatives and further scale their work.

In the immediate moment, however, grantees are simply trying to survive. The sudden shocks of the pandemic, from travel restrictions, supply chain disruptions, and demand limitations, have undercut revenue and left many grantees unable to pay full salaries to their staff or pay rent on office spaces, requiring extreme budget cuts and even layoffs.131 Interviewees were almost universally seeking to access diversified revenue streams that would enable them to continue their operations once their grants ended. They say securing loans from formal financial institutions, getting investments from African and international funders, and accessing wider domestic and foreign markets were key goals. Grantees with sales-based businesses are keen to access interregional and global markets for their products, particularly in countries where specialty goods such as roasted coffee or artisanal goods can be sold at a premium.132

In addition, while grants have provided vital income for most interviewees, particularly those launching new, untested businesses, follow-on loans and investments are needed to finance operations, and build credit and reputation within their countries and on the world stage. Small capital grants and financial support are vital to establishing the businesses and attracting new financial partners and investors, and scaling impact.133

Despite the ongoing challenges, local SMEs are stimulating job creation, economic growth, and community resilience where they are given the support to grow and thrive, as illustrated by analysis on USADF grants. An analysis of available USADF data found that, on average, for every $10,000 invested:

- 25.2 workers were hired through agriculture grants.

- 18.5 workers were hired through youth-led enterprise grants.

- 79.3 people were connected with reliable electricity.134

Quantitative and qualitative analysis of projects across these three sectors suggests the efficiency and effectiveness of the USADF model, which generates locally driven solutions, fosters community involvement, and encourages longer-term ownership over outcomes. The OECD estimates that between 2015 and 2017, the U.S. spent an average of more than $10 billion per year on bilateral aid disbursements to Africa, equivalent to 51% of its total ODA each year.135 While the size of USADF grants is a negligible share, they are multiplying impact: In 2019, USADF’s $25 million investment generated $72 million in new economic activity and reached an estimated 832,000 people.136

In addition, new jobs have cascading impacts in communities. As noted above, multiple studies have found that targeted interventions aimed at increasing job creation, energy access, and agricultural productivity can have multiplier effects at the local and regional levels that lead to greater community resilience and prosperity. Research from the ILO using data from several countries, including Cameroon, Madagascar, Indonesia, and India, found that every job created in a labor-intensive field led to a further one to three jobs being created indirectly.137 Another study looking at 57 sectors in 31 African and South Asian countries uncovered a job multiplier of 7.8 indirect jobs, 5.4 from supply chain effects and 2.3 from wage effects, for each direct job created.138 Also, increasing agricultural productivity affects the broader economy as more people move into more productive and high-income industries such as manufacturing and services as a result of application of more efficient agricultural production practices and relevant technologies that can contribute to higher output.139 These effects—and continued support for agricultural endeavors—are particularly important in light of agriculture’s continued primacy as the largest employer in Africa, and its potential to mitigate food insecurity and increase national GDPs via the growth of other productive sectors.

These findings are also borne out anecdotally by the experiences of USADF grantees, as described throughout this report. The success of WOFAN, the predominantly female rice cooperative in Nigeria, further illustrates the success of USADF’s funding model. Technical assistance has increased agricultural productivity and income, and generated value-added positions in processing, packaging, and marketing. As the cooperative has demonstrated the success of its agricultural techniques—increasing production by 100%—and its ability to sustain reliable jobs that enhance product value, WOFAN has attracted new members, growing from an initial collective of 28 women in 1996 to more than 45,000 members today. The initial USADF investment and support of the founder’s vision has had a transformative impact on the community’s economy and resilience. And in Kenya, a USADF grant awarded to the founder of Afrikapu has led to over 1,000 female artisans in Kenya and South Sudan expanding their businesses to sell their products internationally through microloans, business development assistance, and the creation of an online sales platform.140 Having secured the opportunity to develop her ideas with the support of a knowledgeable institution, and receive training from USADF partners including American business schools and consultancies, Afrikapu’s founder is now passing on what she has learned to other women-owned businesses.

This type of community-focused entrepreneurialism, and the associated multiplier effects, are particularly important in fragile states where the complex intersection of corruption and inequality, poor governance, conflict, and displacement strains local resources and prevents the effective delivery of the goods, services, and infrastructure. As a result, much of the work of government and the private sector has been replaced by interventions from international development institutions, which provide vital aid, but may neglect economic development over emergency response and support for the development of health, education, and other social infrastructure. The 2018 OECD States of Fragility report analysis of global ODA found that only 6% of ODA to extremely fragile countries, and 15% of ODA to fragile countries, was spent on economic infrastructure and services.141 Of grantees interviewed for this report, 74% agreed or strongly agreed that their projects would likely not have been funded if not for USADF’s programs,142 underscoring the vital role this funding model is playing to foster locally driven private enterprise, which grantees view as essential for the long-term growth and stabilization of these fragile states. Follow-on, flexible funding that has allowed grantees to pivot and allocate resources to address immediate, unanticipated needs resulting from the pandemic was also noted as invaluable to business continuity and to the communities.

Expanding USADF’s Impact in a Post‑pandemic World

In light of the pandemic, stakeholders in African development and security will need to innovate and adapt their operations in fragile states where ongoing challenges are, as outlined above, likely to be exacerbated by COVID-19. The USADF model is having a demonstrable impact at the local levels through direct investment in African business and the associated multiplier effects that create jobs and generate economic activity through increased energy access, agricultural productivity, and youth-led enterprise.143 Through open calls for proposals, cultivation of trusting relationships with local staff and organizations, and commitment to building capacity among African entrepreneurs, the USADF model is supporting the development and deployment of tailored, community-driven solutions to the three regions' prevailing problems.

The USADF model presents an opportunity for local entrepreneurs to create solutions to development challenges that are informed by their expertise and lived experiences, rather than imposing a strategy from outside the community, thereby addressing unique local contexts. Also, partnerships with African implementing organizations and the cultivation and support of in-country USADF staff strengthen African-led development, and enable programs to continue running even in exceedingly fragile contexts where international aid workers may be unable to work, as has occurred during the pandemic.144 Grantees concur: among those interviewed, 80% agreed or strongly agreed that USADF funds projects in places and communities where other funders do not.145 Local staff also aid in the growth of trusting relationships among grantees, implementing partners, and the agency, building strong partnerships that support entrepreneurs to create effective solutions, innovate with new approaches, and adjust their funding allocation in response to unexpected events—a flexibility that has become particularly relevant in light of the pandemic.

Opportunities for Partnership and Engagement

Fundamental components of this community-focused model are already driving local impacts and could be further amplified through partnerships with other stakeholders including African governments, local businesses, NGOs, investors, and others within the international development and security communities.

African Governments

Strengthening relationships with regional governments, USADF raised about $28.5 million in funding from African local and national governments, multiplying the size and number of grants awarded through match-funding partnerships between 2015 and 2019.146 These matched funds represent around 19% of the agency’s total investment during that period.147 These types of partnerships provide an opportunity for USADF to increase its investment in entrepreneurship, and for African governments to deploy targeted funds in response to their development priorities. They also increase the impact of these institutions’ interventions, as in the case of a new partnership with the government of Niger to award grants to enterprises tackling food security and agricultural climate resilience among smallholder farmers.

African Investment Community and Private Sector

Public-private partnerships can enable African businesses and investors to expand their reach and raise their profile, while contributing to the growth of African entrepreneurship. Partnerships like that between USADF and South African energy investment group, All On, demonstrate the mutual benefits of such an arrangement: All On is matching USADF and Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) investment in off-grid energy grantees as part of a new Sahel-Horn grant challenge, in a mixed-finance model that will provide awardees with grant funds, loans, and convertible debt.148 Award recipients can begin to establish mixed-funding models that build up credit history and strengthen relationships with African businesses, while USADF and partners like All On can leverage each other’s deep experience and knowledge of the region and active entrepreneurs to maximize impact.

African Non-Governmental Organizations

As part of USADF’s commitment to deploying African-designed solutions to local needs, its network of local implementing partners is key to providing hands-on support to grantees across the three regions, and particularly in fragile contexts where violence and terrorism have inhibited the presence of U.S. aid workers. African NGOs specializing in business development and capacity-building can be a reliable and trustworthy partner for community-led development, while also benefiting from the institutional support of the agency and the wider U.S. government.

International Philanthropic Foundations and Development Institutions

Foundations and development institutions with a focus on agriculture, off-grid energy, and entrepreneurship can partner with USADF to increase the sizes of grants targeting their philanthropic and/or development focus, and augment capacity-building programs by offering their training and expertise to strengthen grantees’ future viability. Established partnerships with GE and Citi Foundation, for example, demonstrate how such relationships can work. Through a donation of nearly $1 million to USADF off-grid energy grants, GE is supporting the expansion of energy access in nine African countries, while Citi Foundation has contributed $1.3 million in seed capital for young entrepreneurs since 2016, and has recently entered into a new partnership focused on young social entrepreneurs in sub-Saharan Africa.149 International investors and philanthropic organizations with limited or no experience operating in Africa can benefit from the expertise and knowledge that USADF and its local implementing partners have cultivated.

International Private Sector

Companies working in relevant sectors, or focused on enhancing business productivity and processes, such as consulting firms, can offer their services at low cost or pro-bono to grantees seeking to professionalize their business structures and staff. Consultancies with an established presence in fragile states or working with experienced nonprofits can multiply their impact by creating coalitions or working groups aimed at addressing systematic challenges to economic development. A new initiative spearheaded by USADF and Bain & Company, for example, is bringing together international nonprofits, philanthropic foundations, and consultants with experience working in agriculture to build food system resiliency by providing pro-bono services to agricultural cooperatives and small businesses in countries where USADF projects are operational.150

U.S. Government International Development Agencies

U.S. government aid agencies can continue to build on their collaborative work in Africa, including via Power Africa, W-GDP, and the Sahel-Horn Off-Grid Energy Challenge, all of which bring together U.S.-based, internationally focused agencies to increase the impact of their development priorities. The Global Fragility Act, now before the U.S. Congress, and its emphasis on targeted interventions in fragile states, presents an opportunity for greater collaboration among U.S. government agencies and the streamlining of efforts based on each organization’s relative expertise and specific strengths.

Looking Ahead

Despite challenges, countries in the Horn of Africa, the Great Lakes, and the Sahel have all made steady progress on numerous development indicators over the past two decades and have demonstrated resilience amid COVID-19. Small businesses and local entrepreneurs are continuing to improve public health, expand their economies, and develop critical job skills to strengthen human capacity by focusing on young people—all while grappling with the effects of corruption, violence, and overall state fragility.

By supporting strategic sectors within fragile countries with small, targeted grants, USADF and its partners—most notably the local entrepreneurs—are having meaningful and lasting impacts at the local level with relatively small per-project investment. Key to all this is USADF’s unique entrepreneur-focused model, which relies on local knowledge and expertise, fosters community engagement, and shows a willingness and commitment to investing in projects and areas that others may not. Other collaborations with public, private, and nonprofit partners, such as those outlined above, stand to amplify their impact and foster greater stability and prosperity for this promising region.

Acknowledgements

FP Analytics would like to acknowledge and thank the many interviewees who shared their insights and experiences for this study, and CS Consulting for their collaboration.

This report was produced by FP Analytics with support from the U.S. African Development Foundation. FP Analytics is the independent research division of The FP Group. The content of this report does not represent the views of the editors of Foreign Policy magazine, ForeignPolicy.com, or any other FP publication.